Rajput Internal Failures in Modern Politics: A Critical Analysis and Way Forward

The political decline of Rajputs (Kshatriyas) in post-independence India is rooted in systemic betrayal—first by Nehruvian socialism, then by Lohiaites and Hindutvadis. While these forces certainly contributed to their marginalization — this narrative remains incomplete without a hard look at internal failures that compounded the community’s political irrelevance.

These failures span across ideological confusion, class fragmentation, lack of institution-building, and a deficit in political imagination within the Kshatriya (Rajput) community.

1. Monarchist Nostalgia and Myth of Aristocratic Utopia

“The crown was taken, but they still expected the throne to be respected.” – This encapsulates the misplaced expectations of former Rajput Royals and Aristocrats

Many Rajput elites, especially from former princely families, retreated into a kind of monarchist individualism post-1947. They mistakenly believed that their inherited cultural capital and past loyalties would convert into political capital in a democratic republic.

- Lack of Institutional Building: While other castes—Brahmins (through academia and bureaucracy) and Banias (through trade and finance)—built robust ecosystems, Rajput elites failed to invest in cultural, educational, or political institutions. Their contributions were ceremonial, not strategic.

Unlike Brahmins (who dominated academia, media, bureaucracy) or Banias (who built business networks), Rajput elites rarely invested in think tanks, journals, political institutions, or cooperatives. Their connection with the masses remained feudal and symbolic rather than democratic or programmatic.

- Tokenistic Electoral Politics: Participation was often limited to individual electoral contests without mass mobilization. There was no investment in cadre-based politics akin to what RSS or Ambedkarite organizations did.

- Blind Loyalty to the Congress or BJP: Many ex-royals naively placed their faith in parties led by the very forces that dismantled their power—first Congress (under Nehruvian socialism), then BJP (under Brahmin-led Hindutva). This reliance was less ideological, more opportunistic and nostalgic.

Rajput royals often aligned with the Congress or later the BJP, naively believing that symbolic gestures would secure representation. In practice, they became tools for vote-banking rather than architects of political direction.

2. Confused Middle-Class : Torn between Hindutva Illusion and Socialist Guilt

“They were too proud to be populists, and too guilty to be assertive.” — a paradox that neutralized political potency.

Post-independence middle-class Rajputs—especially those employed in the army, bureaucracy, or urban professions—drifted towards two contrasting poles:

A. Hindutva Adoption: Many absorbed RSS-style cultural nationalism, hoping for inclusion in a broader Hindu fold. This backfired, as Hindutva ideologues appropriated Rajput valor for propaganda while structurally excluding Rajputs from power.

The post-army and bureaucratic middle-class Rajputs gravitated towards the RSS-BJP framework, seeking respectability through Hindu unity. But Hindutva used Rajput imagery (Maharana Pratap, Shivaji, etc.) for populist narratives while excluding actual Rajputs from ideological or organizational power.

- Instrumentalization without Representation: Rajputs became poster-boys for temples and war-memorials, but were given no role in intellectual leadership or ideological framing.

- Suppressing Caste Assertion: Under Hindutva, caste identity was discouraged unless it served mobilization. This depoliticized Rajput assertion at a time when OBCs and Dalits were asserting themselves institutionally.

B. Lohiaite & Leftist Guilt Complex: Some middle-class Rajputs in academia and bureaucracy internalized Lohiaite socialism and Marxist historiography, which cast Rajputs as feudal oppressors.

- Resulting in Silence or Shame: Instead of asserting a counter-narrative, these Rajputs self-censored their own history and failed to build alternative intellectual currents. This led to a disowning of community heritage, resulting in silence or even collaboration with anti-Kshatriya narratives in the name of “progressivism.”

- Estrangement from Rural Kins: This class did not maintain ties with their rural Rajput base, unlike Ahirs , Jats, or Marathas whose middle classes often returned to mobilize their caste brethren. These middle-class Rajputs failed to serve as bridges between the elite and the rural Rajput base. Unlike the Jat, Ahir, or Maratha middle classes, they neither led mass mobilizations nor created intellectual forums for their community.

3. Ideological Vacuum: Neither Traditionalism nor Modernism

1. No Post-Independence Kshatriya Ethos:

Rajputs lacked a coherent political ideology to adapt to the modern Indian polity.

While Dalits had Ambedkarism, OBCs had Mandalism, and Brahmins had Hindutva, Rajputs lacked a guiding ideology. There was no articulation of a post-feudal Rajput identity compatible with democracy, justice, and modern politics.

2. Romanticism without Realism :

Rajputs celebrated historical symbols but failed to contextualize them in the present. Maharana Pratap or Prithviraj Chauhan remained emotional references without policy direction or political strategy. The disconnect between tradition and modernity was not resolved:

- Royalist Rajputs stuck to pre-modern symbolism without socio-economic programs.

- Middle-class Rajputs lacked courage or conviction to define a modern, justice-based Kshatriya ethos rooted in regionalism and republicanism.

3. Electoral Opportunism Over Movement-Building:

Rajput participation in elections remained personality-driven. Leaders fought for tickets rather than building organizations. There were no federations, unions, or think tanks rooted in the community.

4. Structural Weaknesses and Lack of Ecosystem

A. No Media , No Academic Ecosystem, No Narrative:

No Rajput-dominated media, publishing house, or intellectual forum to promote their historical narratives or contemporary concerns.There is no major media house, publishing network, or digital ecosystem controlled or even influenced by Rajputs. This left the community voiceless in the battle of ideas.

B. Scattered and Competitive Leadership:

Rajput leaders often undercut each other, seeking individual relevance in national parties rather than community empowerment. Rajput leaders often worked at cross-purposes, sabotaging each other in pursuit of individual relevance. There was little commitment to a collective strategy.

C. Failure to Forge Alliances:

No lasting alliances were formed with fellow peasant-warrior communities like Marathas, Ahirs or Malis—despite shared grievances.Each fought separately against a common Brahmin-Bania state apparatus.

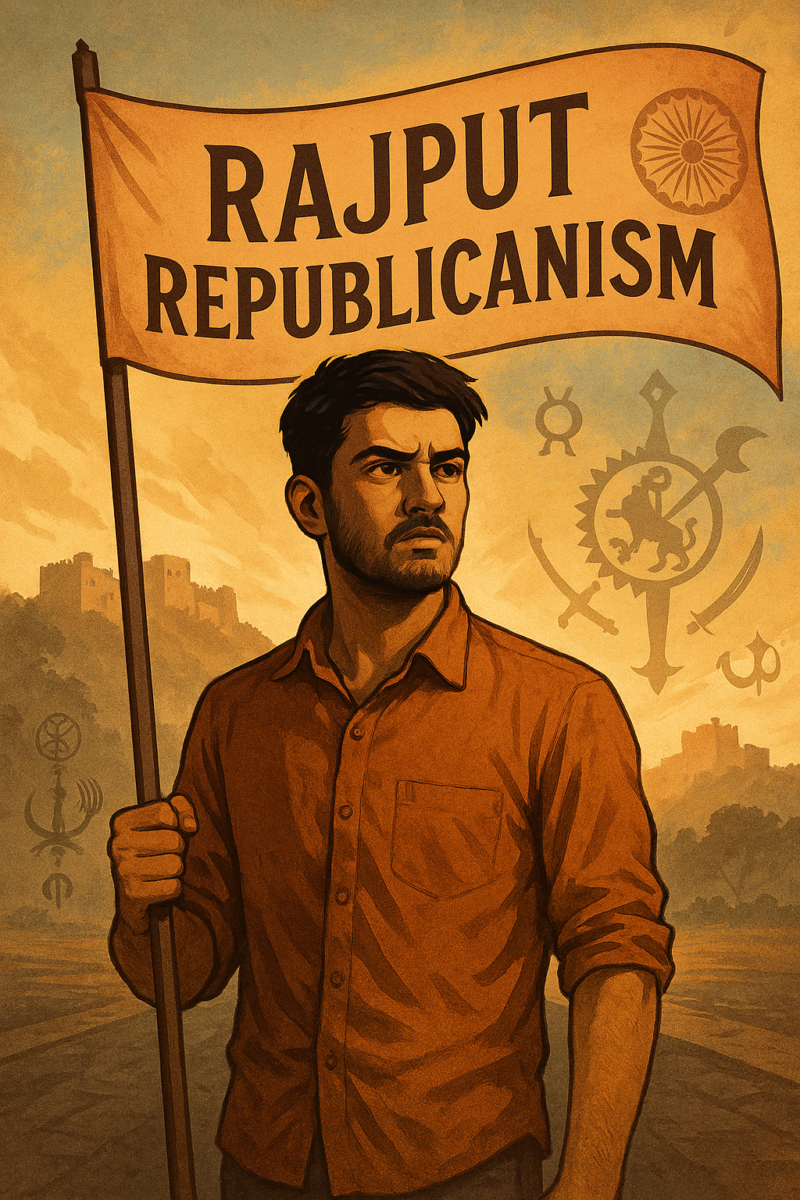

5. The Way Forward: Rajput Regional Republicanism

Rajput resurgence will not come from reclaiming lost royal privileges or mimicking Brahmin-Bania ideological models. It requires a new political and cultural paradigm rooted in regional strength, caste solidarity, and democratic values. This vision must include the following elements:

1. Ideological Reconstruction

- Develop a Republican Kshatriya Ethos that fuses dignity, justice, and regional identity.

- Move away from monarchist nostalgia and towards a people-centric, agrarian nationalism rooted in Rajputana’s rural values.

- Articulate a political philosophy that asserts dignity without domination—a Kshatriya-hood of responsibility, not privilege.

2. Institutional Ecosystem Building

- Invest in think tanks, academic journals, history forums, youth organizations, and regional political schools.

- Establish a Rajput Media Collective to counter mainstream distortions and push original research and opinion.

- Create cultural institutions that teach Rajput history and regional languages with pride.

3. Alliance Formation with Peasant-Warrior Castes

- Forge ideological and electoral alliances with Marathas, Malis, Gujjars, Ahirs, and Kamma/Reddy communities.

- Advocate for a new agrarian federalism that prioritizes farmers, veterans, and rural artisans.

- Counter both Brahmin-Bania capitalism and Jat-style caste hegemony through solidarity-based federal politics.

4. Political Mobilization and Cadre-Building

- Build cadre-based political organizations at the district and panchayat levels.

- Promote local Rajput leadership with training, education, and ideological clarity.

- Move beyond elections—engage in social service, protests, journalism, and legal activism.

5. Intellectual Reclamation

- Develop alternative historical narratives to counter colonial and Marxist distortions.

- Reclaim figures like Rana Sanga, Durgadas, Rao Gopaldas, Jaychand, Mansingh, Amar Singh Rathore from misrepresentation.

- Encourage young Rajputs to enter academia, media, law, and policymaking.

Conclusion

The future lies not in reviving past grandeur but in forging a bold, just, and modern Kshatriya consciousness—democratic in spirit, regional in grounding, and revolutionary in aspiration.