Nehruvian Socialism: Brahmin-Bania Raj, Jat Fascism & Dismantling of Kshatriyas

The early decades of post-independence India are often portrayed through the lens of Nehruvian socialism—a supposedly egalitarian effort to dismantle feudal structures, redistribute wealth, and lay the foundation of a modern democratic state. However, a closer look at the implementation of these reforms reveals a different picture: one where socialist rhetoric masked a consolidation of caste and class power, primarily benefiting Brahmins in bureaucracy, Banias in industry, and Jats in rural politics, while systematically disempowering the Rajputs—socially, politically, and economically.

I. Brahmin Hegemony in National Institutions: Was Nehru A Casteless PM?

Despite Nehru’s professed commitment to secularism and equality, Brahmins continued to dominate India’s key institutions during his tenure:

- Chief Ministers and Central Bureaucracy: Most of the early Chief Ministers in major states were Brahmins—Govind Ballabh Pant (UP), B.C. Roy (Bengal), C. Rajagopalachari (Madras), and Ravi Shankar Shukla (MP), among others. The ICS/IAS cadres also remained Brahmin-dominated well into the 1960s.

- Cultural Policy and Education: State patronage of Sanskritized, Nehruvian secularism ensured Brahminical cultural dominance was preserved under the guise of national integration.

- While Rajput martial culture and regional heritage were sidelined or depicted as feudal relics, Brahminical frameworks were institutionalized in academia, policymaking, and the judiciary.

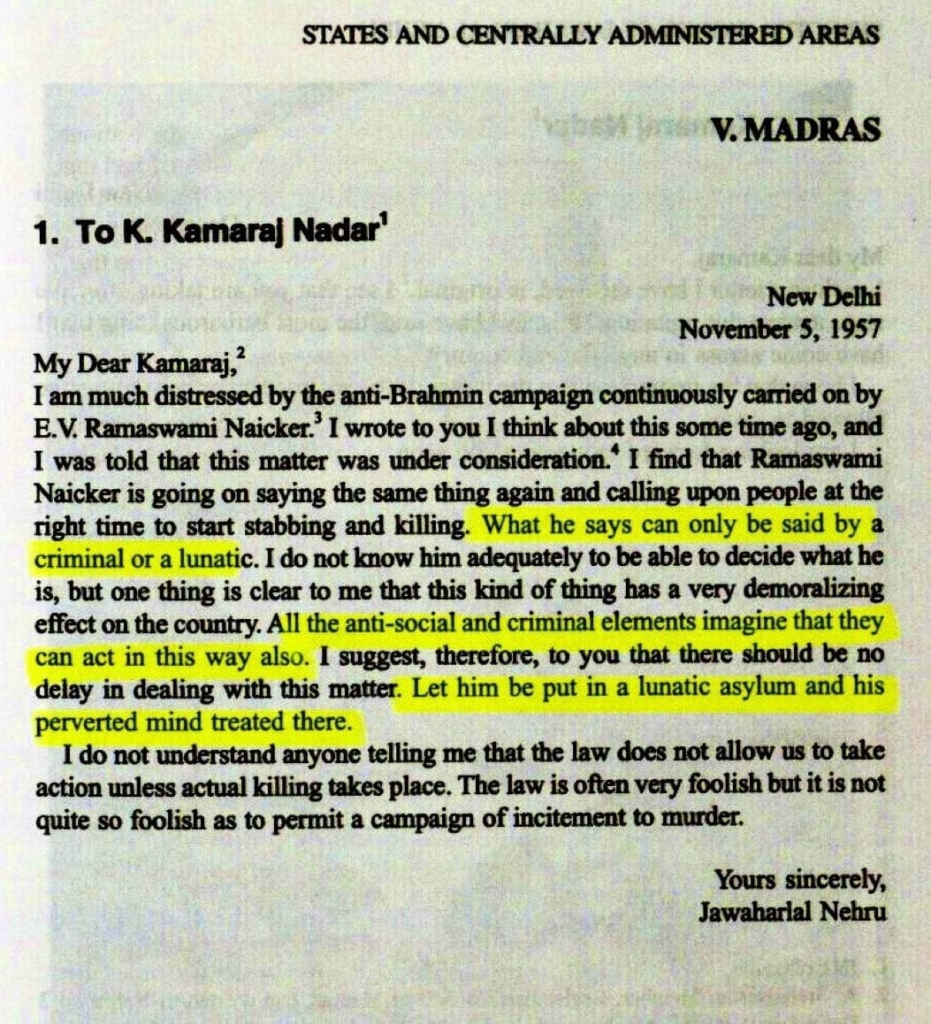

Nehruvian Intellectuals, mostly Upper-caste Brahmins , Banias, Kayasths & Khatris – to this day stereotype, denigrate & otherize the Rajputs through different institutions – rationalizing anti-Rajput propaganda by using different ideologies – liberalism, socialism, anti-Caste . However, contrast that with Jawaharlal Nehru’s defense of his own Brahmin identity and Brahmin community.

II. Promoting Interests of Capitalist Bania Allies: An Overlooked Contradiction

Nehru publicly criticized capitalism and promoted a mixed economy, but he did not confiscate wealth from industrialists like Birla, Bajaj, or Dalmia. Instead, he: Nehru’s economic policies were supposedly “socialist,” but in practice they protected and promoted established Bania capitalist houses:

- Industrialists like GD Birla, Jamnalal Bajaj, and the Mittals were never truly threatened by Nehru’s planned economy. On the contrary, they were part of his advisory circles and benefitted from license raj mechanisms that restricted competition while preserving monopolies.

- Nehru relied on them for nation-building efforts, funding government institutions and backing industrial growth. Nehru introduced the License Raj, which ironically protected the interests of big Bania industrial houses and created monopolies.

-

This gave rise to the perception—and reality—of a cozy relationship between the Congress leadership and certain capitalist families, despite the socialist rhetoric.

- Nehru targeted landed aristocracy (largely Rajput and other warrior lineages) rather than capitalist elites, allowing Bania-led industrial and trading houses to consolidate control over key sectors with the blessings of the state. So yes, Nehru’s socialism was harsher on Kshatriya landholders than on industrial capitalists. Whether this was a pragmatic compromise or ideological inconsistency is still debated, but the Rajput grievance that their class was disproportionately dismantled is not unfounded.

The Nehruvian Intelligentsia cleverly projected a politically cornered & predominantly plebian Rajput community as the oppressors in the Socialist Narrative, even as it promoted the institutional hegemony of Brahmins and capitalist hegemony of Banias.

While the Dalit-Ambedkarite and Dravidian movements rightly identified the Brahmin-Bania nexus as the cornerstone of India’s oppressive caste hierarchy, the Nehruvian worldview curiously fixated on portraying the Rajputs as the principal villains of feudalism. This selective historical framing not only deflected scrutiny from entrenched Brahminical and capitalist dominance but also justified the systematic dismantling of Rajput socio-political institutions under the guise of socialist reform. Even today, this Nehruvian lens continues to shape the narrative frameworks of India’s urban liberal elite—echoed in academia, media discourse, and popular culture. From classroom syllabi to editorial pages, and from mainstream cinema to bestselling literature, the vilification of Rajput identity persists as a convenient trope, while the actual hegemonic structures remain largely unchallenged.

III. Jat Feudal Hegemony in Rural Politics: Nehruvian Double-Standards

Perhaps the most glaring contradiction of Nehruvian socialism was the non-confrontation with powerful Jat landowners, especially in regions like Western UP, Haryana, Punjab, and parts of Rajasthan:

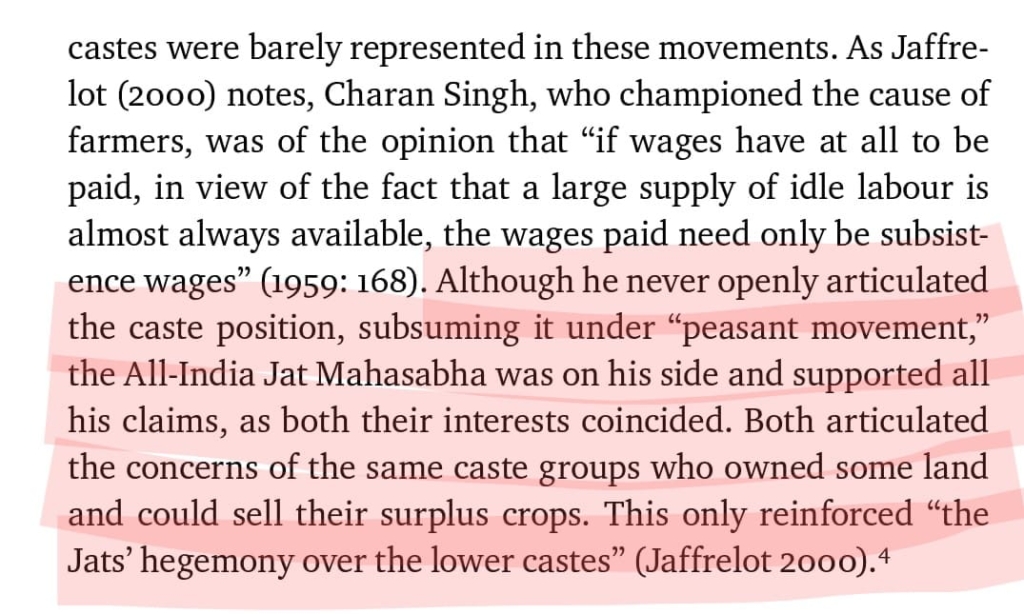

- Jat landowners held massive agricultural estates, especially in the regions of the current National Capital Region since late Mughal-era, but were often exempted from the full impact of land reforms because they were presented as “self-cultivating peasants” by the Congress politicians, notwithstanding their use of landless Dalit cultivators for farm labour.

- On the contrary, Rajputs as a whole were stereotyped as “Feudals or Samants” in the Nehruvian worldview – a position still held by the Congress intellectuals to this day. Hence, while a Jat Zamindar or a Feudal was still a kisaan, a Kshatriya (Rajput) farmer with much less landholding and lower social class, was ineligible to be counted as kisaan – rather he was a samant by virtue of his caste. While Rajput jagirdaars were stripped of land and political clout, Jat dominance grew unchecked, eventually solidifying their hold over local politics through caste-based mobilization and state patronage

2. Political Power & Mobilization:

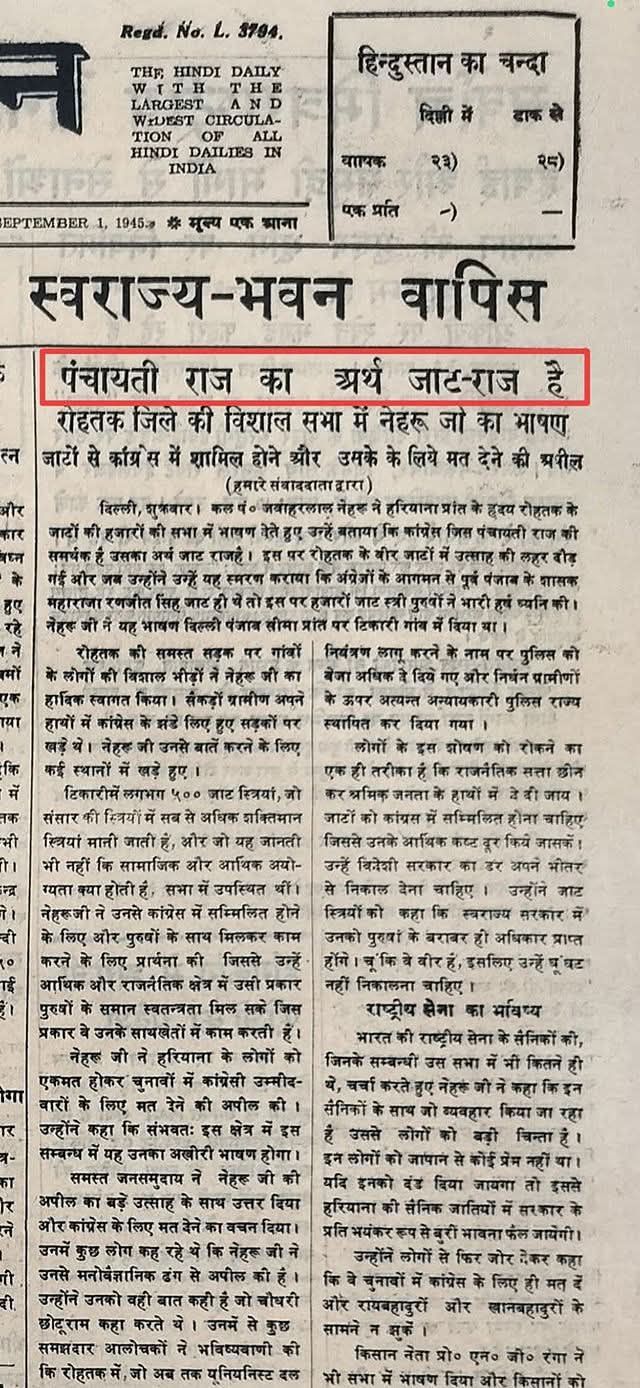

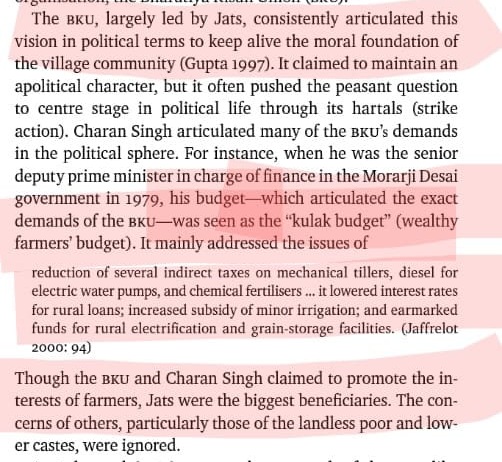

- In Punjab, Haryana, Western UP, and parts of Rajasthan, Jats were politically well-organized and began asserting their influence through agrarian movements and electoral politics.

- Nehru and the Congress party relied on Jat leaders for rural vote banks, especially as they transitioned into democratic politics.

- As a result, there was less political will to confront or alienate them.

3. Strategic Electoral Calculus:

- Jats were emerging as dominant peasant castes in northern India, and the Congress needed their support in rural constituencies.

- Targeting them would have undermined the party’s rural base—so reforms often ignored large Jat landholdings, even when they were as feudal in nature as others

- Rajputs were also politically less organized as a democratic vote bloc at the time, compared to the growing influence of Jat peasant unions and kisan sabhas.

4. Selective Socialist Justice

- Nehru’s land reform policies claimed to be class-based, yet their selective implementation had strong caste implications.

- Jats, despite holding significant land and local power, were not subjected to the same structural dismantling as Rajputs or even some Brahmin landholders in other regions.

- This reinforced the rise of dominant caste politics, where communities like the Jats expanded their economic base and used democratic representation to entrench local hegemony.

5. Jaundiced Sociology

- Nehruvian liberals prefer to look the other way round & even promote Jat Fascism (like normalizing terms like Jatland), while they refuse to respect the dignity and agency of Rajputs – including denying them a respectable voice on their own history and socio-political issues.

Historically, Rajputs were a diverse confederation of warrior clans, while the term “Jat” referred more fluidly to agrarian communities in northwestern India. Over time—particularly under Mughal and later British rule—many Rajputs were displaced from their traditional positions, becoming peasants, pastoralists, or even bandits. In contrast, a significant number of Jats rose in status as courtly officials, revenue collectors, and “Chaudharies” under new administrative arrangements. However, Nehruvian sociology conveniently overlooks this complex historical evolution, reducing Rajputs to a monolithic category of “feudal lords” (samants), while idealizing Jats as noble “kisaans”—a simplification that has found acceptance across both liberal and right-wing policy circles.

This jaundiced framework shields the entrenched privileges of Jat elites—be they zamindars, businessmen, or regional political oligarchs—while recasting their caste-based dominance and aggressive mobilization as legitimate “subaltern rebellion” or “peasant assertion.” The silence of civil society on inflammatory anti-Rajput rhetoric—such as remarks made by leaders like Hanuman Beniwal—highlights this double standard. Meanwhile, the lazy equivalence between Rajput identity and aristocratic oppression has been weaponized to justify caste-based hostility, delegitimize Rajput grievances, and deny them space in public discourse. Worse still, it has served to erase or malign their collective identity, historical contributions, and cultural heritage.

In effect, the Nehruvian lens asks society to treat Rajputs as the French Revolution treated the European aristocracy—not as citizens with history and agency, but as relics to be derided, silenced, and swept away in the name of progress. This framing, though cloaked in the language of justice, is itself deeply unjust—and must be questioned.

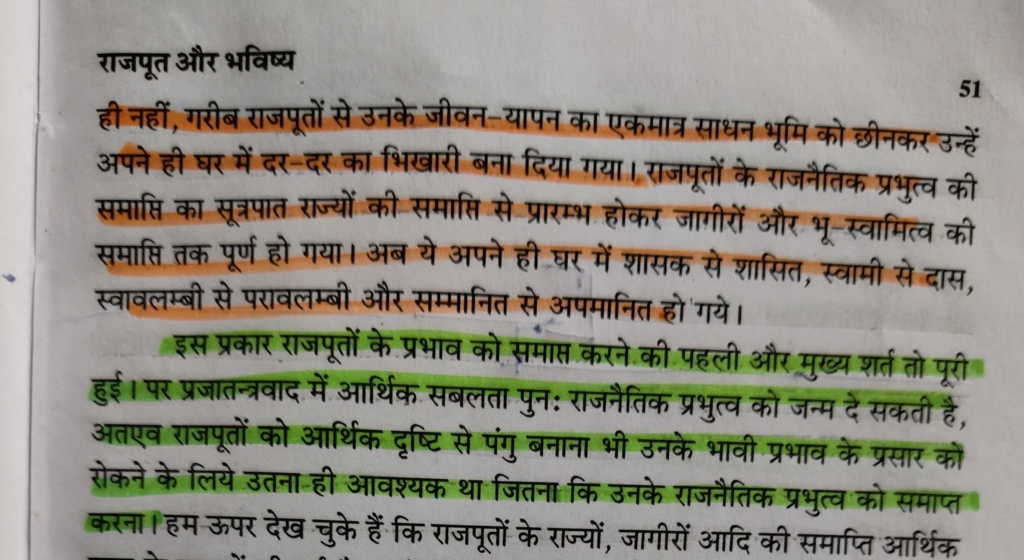

IV. Targeting the Rajputs: Dismantling a Historical Community

Nowhere was the selective nature of Nehruvian reform more evident than in its treatment of the Rajputs:

- Abolition of Jagirdari disproportionately affected the Rajputs, severing their economic base and severing access to land, their key form of capital.

- The disbanding of State Armies robbed them of symbolic and functional power, branding them as remnants of a bygone era.

- The State interfered in Rajput-managed educational, cultural, and religious institutions, including disruptions like the Chopasni School Andolan, further breaking their community structures.

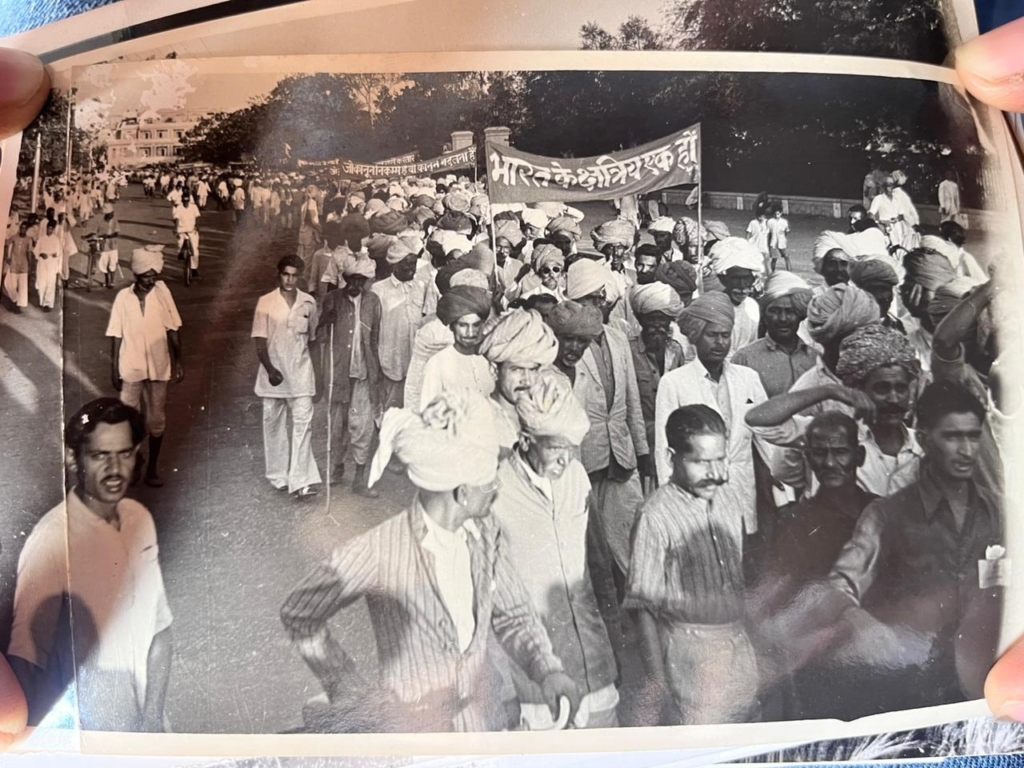

- The Bhuswami Andolan saw Rajput landholders, many of whom were not feudal oppressors but rural gentry and cultivators, struggle to preserve land and dignity amid laws that redistributed land without support or compensation.

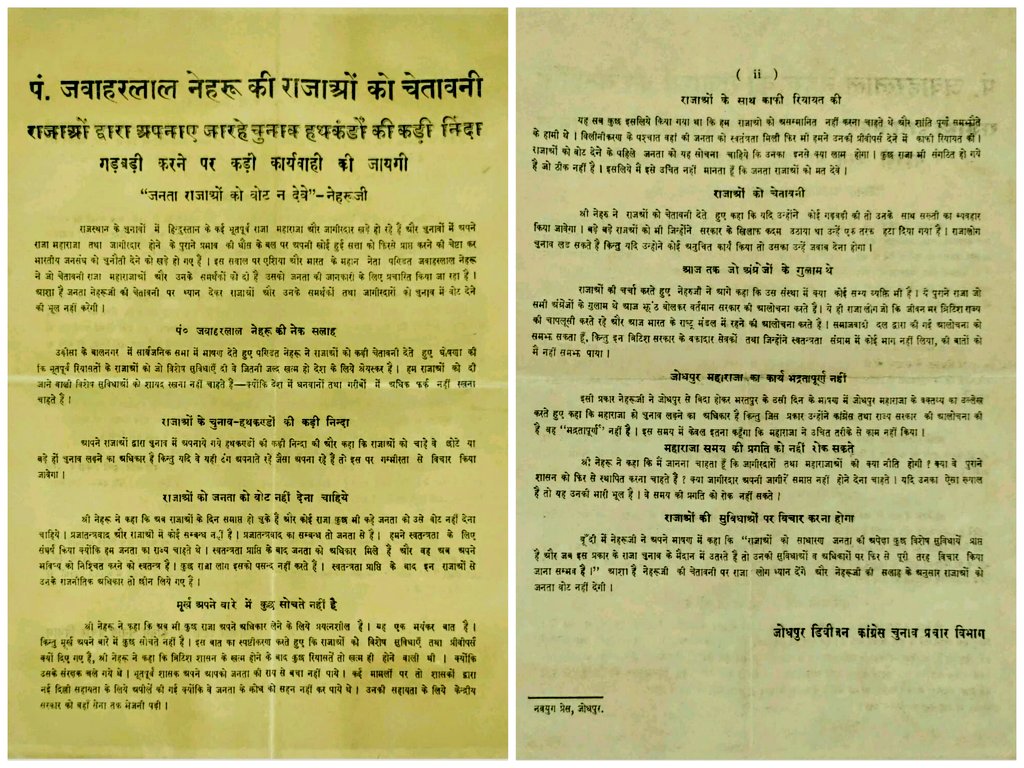

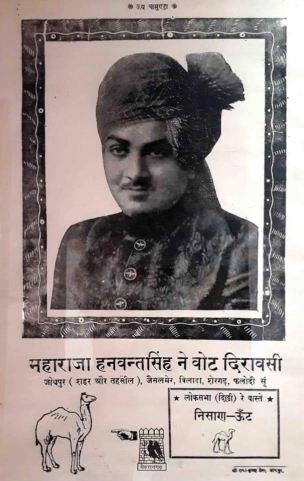

V. Maharaja Hanwant Singh Rathore: A Silenced Voice

Against this backdrop, Maharaja Hanwant Singh Rathore of Jodhpur emerged as a rare and courageous Rajput voice attempting to reclaim agency through democratic means. After being reduced to a ceremonial title by the state, he:

- Founded the Rajasthan Sangathan, which was a political attempt to unite Rajputs and allied communities against Congress authoritarianism.

- In the 1952 general elections, his party achieved spectacular success, especially among Rajputs, rural subalterns, and kisans, revealing the undercurrent of resentment against the Nehruvian project.

- His sudden death in a plane crash hours after his electoral victory remains unexplained, and to many, represents not just personal tragedy but a systemic suppression of a growing anti-Congress movement.

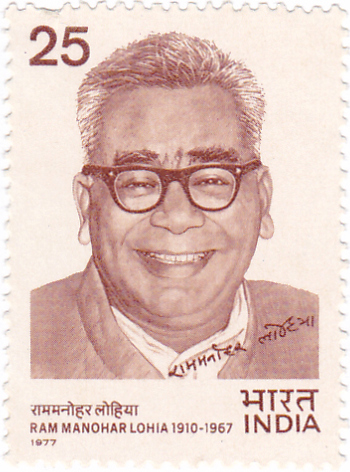

VI. Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia: The Bridge Between Nehru, Jats & Banias

Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, a Marwari Bania, though a socialist critic of Nehru, ironically facilitated the empowerment of Jat and Ahir feudals in North Indian politics:

Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, a Marwari Bania, though a socialist critic of Nehru, ironically facilitated the empowerment of Jat and Ahir feudals in North Indian politics:

- Lohia championed non-Congress socialist mobilization, but much of it drew strength from dominant peasant castes like Jats and Ahirs who retained local feudal power.

- He opposed Brahminism rhetorically, but the new power structure he helped shape ended up empowering Jat-Ahir landlordism in rural India without dismantling economic hierarchies.

- Thus, a new caste oligarchy emerged, where Lohia’s caste-based politics allied with Bania capital and feudal landowners from backward castes—leaving upper-caste but landless or politically weakened Rajputs outside the emerging coalition.

VII. Conclusion: Selective Socialism, Systemic Casteism

The Nehruvian project, far from being uniformly socialist, was selectively punitive and ideologically inconsistent:

- It preserved Brahminical influence in institutions,

- Empowered Bania capitalists through state-sanctioned monopoly capitalism,

- Entrenched Jat-Ahir rural dominance via caste politics,

- While it crippled the Rajputs—once a proud martial and administrative class—by destroying their social capital, land holdings, and political institutions.

In this light, Rajput marginalization was not collateral damage, but a central outcome of Nehruvian policy—a case of state-sponsored caste restructuring under the veil of egalitarian socialism.