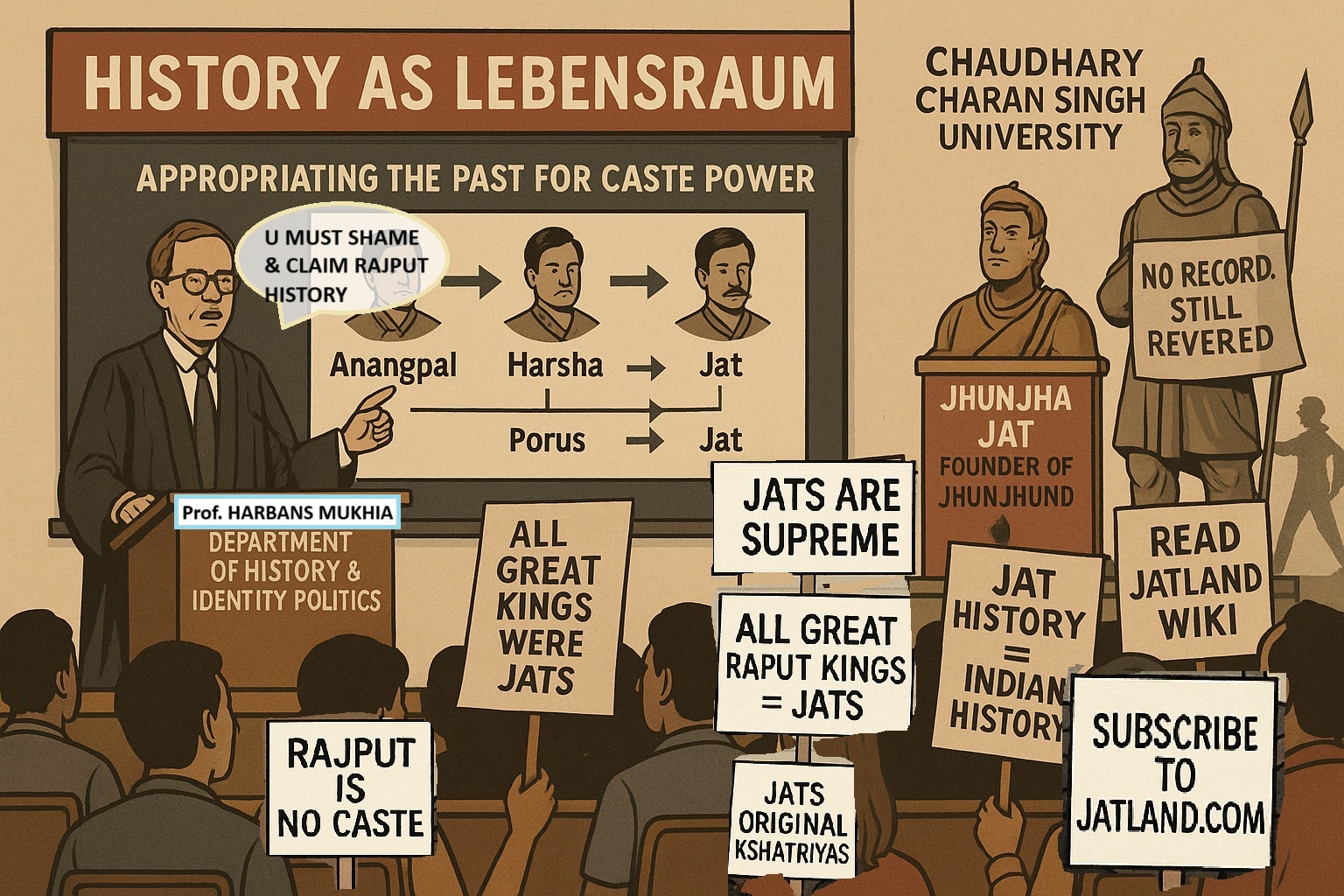

History As Social Lebensraum: Jat Disinformation On Rajput History

I. Introduction: Jat Concept of Historical ‘Lebensraum’

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Arya Samaj movement, under the leadership of Dayanand Saraswati and later Swami Shraddhanand, initiated a campaign to “Kshatriya-ize” the Jats, in an attempt to integrate them into the Brahmin-Bania political struggle to socially delegitimize the Kshatriyas or Rajputs. Post-Independence, under Jawaharlal Nehru’s “socialist” framework, a significant economic shift took place : land and economic capital was transferred from Rajput landholders to Jats, making them the new economic elite—with Brahmin-Bania legal and political support.

Lohiaite Socialism, which gained dominance in the post-Mandal era, romanticized the feudalism of Jats, Gujjars, and Ahirs as symbols of an egalitarian rural society, while continuing the dismissive portrayal of Rajputs—a legacy inherited from the Arya Samaj, Praja Mandals, Congress, and the RSS. The persistent depiction of Rajasthan, Haryana and Western Uttar-Pradesh as “Jatland” by the mainstream media exemplifies this romanticization. This narrative normalized Jat rural hegemony, concealing the power networks of Jat zamindars allied with Brahmin politics and Bania capital. In contrast, it justified the political persecution and social marginalization of Rajputs, creating fertile ground for the current wave of Jat-led disinformation and appropriation of Rajput history.

The modern Jat narrative represents one of the most aggressive forms of historical distortion in contemporary India. With neither the political patience to record history honestly nor the philosophical burden to reconcile contradictions, the Jat approach to history has become an instrument of power—rewriting the past not for truth, but for territorial and caste-political expansion. Jat elites have developed a dual strategy: weaponizing victimhood when it suits political mobilization, while simultaneously appropriating Rajput martial legacy and Kshatriya identity for cultural supremacy. Their historiography is not rooted in accuracy but in opportunism—treating history as “Lebensraum” to be conquered, colonized, and weaponized. This expansionism is not just intellectual, but deeply symbolic and political—a calculated annexation of the identities and legacies of various Rajput or Kshatriya clans, accompanied by sustained efforts to vilify and marginalize Rajput masses in the present.

II. Contradictions in Identity As A Political Strategy

At the heart of Jat historical distortion lies a fundamental contradiction: they claim to be oppressed Shudras who suffered under Rajput Samantvad, while simultaneously asserting themselves as the original Kshatriyas for which they lay claims on Rajput lineages, heroes, and clans.

1. The Fabrication of Serfdom and the Invention of ‘Perpetual Oppression’

As “oppressed Shudras”, Jats claim historical oppression under “feudal” Samantvad of the Kshatriyas, often projecting the Rajput community itself as casteist overlords — even in the present severely altered socio-political setup. to tap into the OBC reservation discourse and the narrative fuels their political alignment with OBC-Bahujan formations and justifies OBC reservation demands. They use this grievance-based rhetoric of Shudra victimhood at Kshatriya hands to demand quotas under OBC category and dominate Bahujan politics, to which they were once outsiders

Jat political rhetoric, especially in Rajasthan, Haryana, and Western UP, frequently deploys a grievance narrative of being “long oppressed by Rajput Samants”—portraying Jats as peasant castes crushed under a brutal feudal system. Terms like Samantwad and Thakurwad have been selectively weaponized in electoral campaigns and public discourse to demonize Rajputs, regardless of the actual local power dynamics, which in many regions have been dominated by Jats for decades.

However, this narrative collapses under scrutiny. In much of rural Haryana and Western UP, Jats have historically functioned as the landed gentry, exercising near-total control over agriculture, panchayats, and caste-purity norms. Far from being oppressed tillers, they were the Zamindars, Chaudharies, and Khap rulers—enjoying hereditary power and using violence to enforce social hierarchy, particularly over Dalits and non-dominant OBCs

2. Boasting Zamindari Status While Weaponizing Serfdom

Perhaps the most glaring contradiction in Jat caste discourse is the simultaneous glorification of their status as Big Zamindars and land-owning farmers, while also invoking a false memory of socio-economic serfdom to extract electoral sympathy.

- As “Kshatriyas”, Jats boast of being “Big Zamindars”(large landowners), and warrior-community that resisted Mughals and British alike. While their Arya Samaj-era oral traditions are replete with claims of descent from various Rajput lineages — in the post-Mandal-era , mythic retellings, false genealogies and misplaced sociological theories were popularized by Jat-Brahmin academicians to facilitate forceful appropriation of entire Rajput clansl ike the Tomars, Bhattis, Yaduvanshis, Parmars , Johiyas and even Bais— into Jat identity . In this guise, they portray themselves as indigenous martial rulers, often delegitimizing Rajputs from their own ethnic heritage.

- Jat leaders in Western UP and Haryana frequently refer to their community as the “backbone of India’s agrarian economy,” “the land-owning class,” or “peasant warriors.”

- Yet the same leaders also mobilize under OBC banners demanding reservations, citing “centuries of oppression”—an argument that conveniently ignores the violent landlordism they historically practiced against Dalits and tenant communities.

This contradiction is not just theoretical—it has tangible political consequences. It has allowed Jat leaders to dominate the OBC discourse, claim backward-class benefits, suppress non-dominant OBCs, and frame themselves as both victim and victor, depending on which position yields more social capital.

A Brief Summary of their Claims

| Claim | Contradiction |

|---|---|

| “We are Shudra peasants” | But also “We are the Zamindars and original Aryan Kshatriyas” |

| “We hate feudalism” | But glorify our Chaudharies, Khaps, and claim Rajput dynasties |

| “We are OBC” | But resist any sub-categorization that might benefit smaller castes |

| “We fight for Bahujans” | But silence Dalit protests and block Bhim Army rallies |

This shape-shifting identity—oscillating between agrarian backwardness and martial superiority—is not confusion; it is a calculated strategy of caste-politics. It allows Jats to extract both affirmative action benefits and cultural legitimacy, while simultaneously undermining the Rajput claim to Kshatriyahood and ensuring State-Civil society hostility of the towards them.

III. Appropriation of pre-Islamic Kshatriya (Rajput) History

In recent years, Jat-centric writers, caste websites, and social media influencers have begun claiming ancestry from early medieval and ancient Kshatriya kings, with no historical or epigraphic evidence. The objective is clear: displace Rajputs from their own cultural ancestry by retrofitting Jat identity into pre-modern royal histories.

Some notable examples of this aggressive appropriation include:

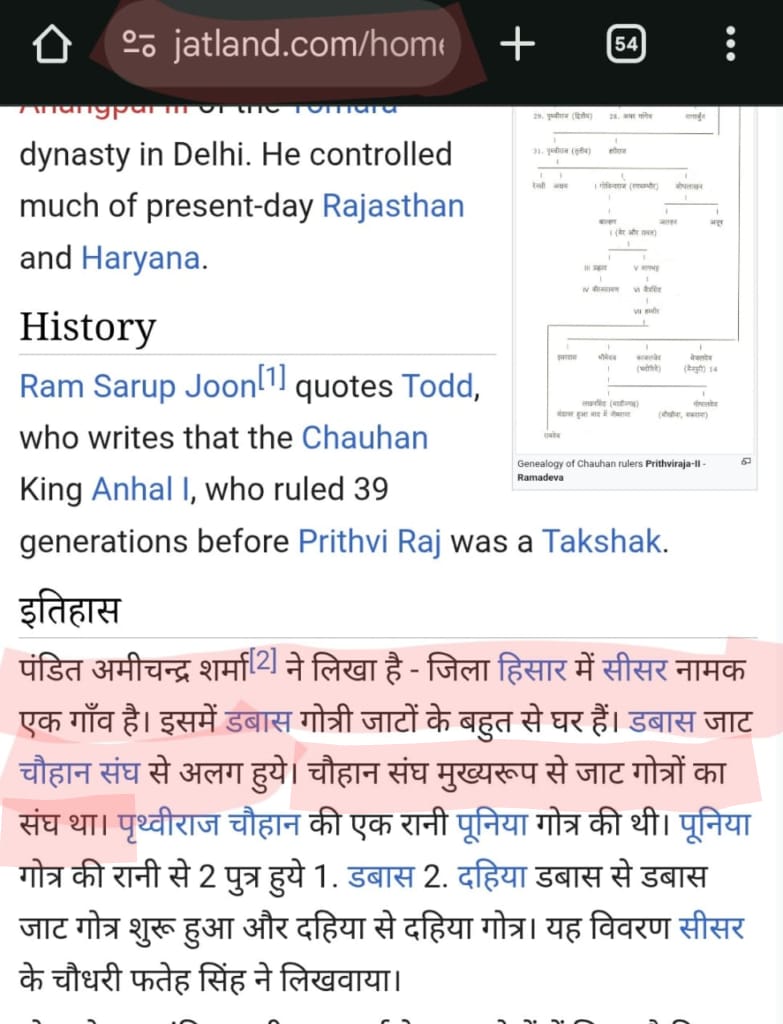

- Anangpal Tomar (founder of Delhi and scion of the Tomar Rajputs): Now increasingly claimed by Jats as “Anangpal Jat” despite centuries of Tomar association with Rajput identity and recorded epigraphic traditions and cultural associations with other Rajput clans.

- Emperor Harshavardhan Bais (7th century): A legendary ruler from the Bais Rajput lineage of Thanesar, now dubiously incorporated into Jat histories as a “Jat Kshatriya king” in caste publications and regional pamphlets. Noting absence of Jats in the Kannauj belt, their claims of having had a King who ruled from that city is historically bizarre – particularly since the Kannauj district hosts many villages and kasbas of Bais Rajputs.

- Yashodharman Aulikara (6th century Malwa king who defeated the Hunas): The Aulikara dynasty is being rewritten in some neo-OBC circles as having “agrarian roots,” undermining its clear inscriptional association with Kshatriya identity and Rajput cultural memory. Their hollowness of their claim on Yashodharman is conspicuous with their near-historical absence and demographic redundancy in the Malwa region.

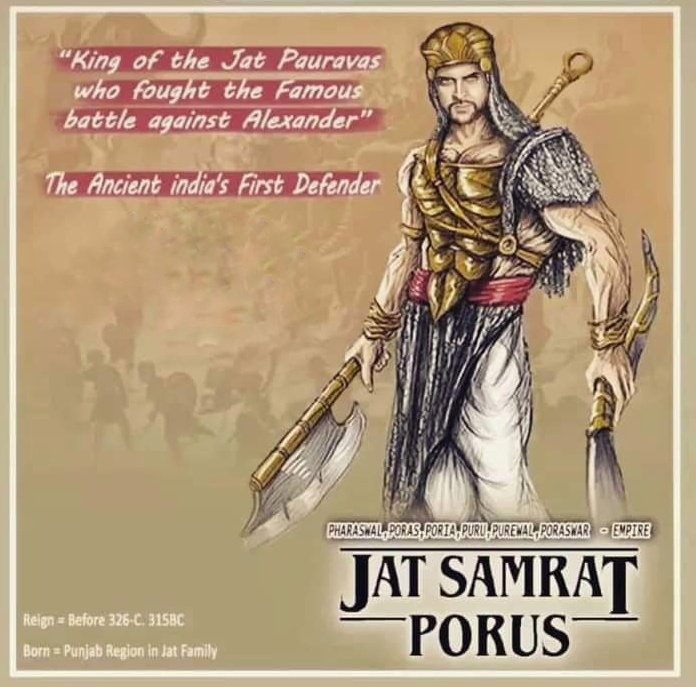

- King Porus (Purushottam of the Katoch lineage): Although traditionally linked with the Katoch Rajputs of Trigarta (Himachal region), Jat-centric narratives now attempt to reframe him as a “Jat warrior king” who resisted Alexander—ignoring both geography and clan lineage.

- Jamboji Panwar, also known as Guru Jambheshwar, was a 15th-century Rajput saint and environmental philosopher from the Panwar (Parmar) Rajput clan of Rajasthan. He founded the Bishnoi sect, known for its deep commitment to nature conservation and non-violence. Historically revered as a Rajput spiritual reformer, Jamboji’s legacy has recently become a target of appropriation by Jat caste groups, who attempt to reframe him as a Jat figure—despite his clear Panwar Rajput lineage.

- Apart from the above, many Hindu Jaat chauvinists in India, popularly appropriate Muslim Rajput figures of pre-partition Punjab — Dulla Bhatti, Rai Ahmad Khan Kharral, Malik Khizr Hayat Tiwana, Abdus Salem — and project them as Jats to the Indian public with little scrutiny, since the Rajput descendants of these figures live in Pakistan.

These cases show how Rajput clans, dynasties, and civilizational contributions are being strategically co-opted to construct a fake continuum of Jat martial greatness—without any textual, inscriptional, or bardic evidence. Entire Rajput clans like the Tomars, Bhatis, Chauhans, Yaduvanshis,Johiyas, Parmars,Janjuas and Bais are absorbed into Jat caste-histories with no historical basis. This is not inclusion; it is historical annexation—displacing Rajputs from their very lineage and history.

IV. Digital Disinformation: The Case of Jatland.com

A crucial hub in the ecosystem of online disinformation is Jatland.com—a community wiki that masquerades as a historical archive and encyclopedia. This website:

- It fabricates clan linkages and genealogies by forcefully inserting Rajput clans into Jat Identity.

- Presents false military histories to claim that Jats were the original defenders of India against Turks and Mughals. It distorts historical events, military victories, and ancient kingships to center Jats in every significant Indian moment—from the Mahabharata to the 1857 Revolt.

- Spreads conspiracy theories about how Rajputs “stole” Kshatriyahood from Jats during the medieval period.

- Aggressively hosts coordinated efforts to edit Wikipedia and push Jat-centric narratives into mainstream history consumption—spreading falsehoods among students, UPSC aspirants, and young readers with no access to primary historical sources.

V. Jat Historians and Academic Legitimization

This distortion is not limited to folklore or WhatsApp forwards. Prominent Jat-origin historians have played key roles in legitimizing anti-Rajput narratives under Marxist and subaltern frameworks:

1.Harbans Mukhia, the former rector of JNU and a prominent Marxist historian of Jat origin, has consistently exhibited a deep-seated bias against the Rajput community in both his academic work and public commentary. His writings and interviews reveal a pattern of systematic erasure and delegitimization of Rajput history, identity, and political agency.

One of the most telling instances of this bias came during a BBC Hindi interview, where Mukhia dismissed the Rajputs outright, claiming that they played “no role in the anti-colonial struggle or the making of modern India.” This sweeping generalization is not only historically inaccurate, but also politically loaded, aimed at reducing an entire pan-Indian community to irrelevance.

Mukhia’s academic work follows a predictable pattern—he attempts to portray the Rajput identity as a “constructed” and “imagined” order, emerging only after the 12th century from a mixture of tribes, castes, and elite aspirants. While partially borrowing from the Dirksian model of colonial reification of caste identities, Mukhia hollows out the legitimacy of Rajput clan-kinship systems, portraying them not as organic social identities rooted in centuries of local and regional statecraft, but as artificial constructs rooted in “feudalism”. On one hand this ideological framing stereotypes the Rajputs by misreprsenting feudalism and Rajput identity as mutually-exclusive — a stereotype that has armed anti-Rajput narrative-making by politicians and public intellectuals alike. On the other it provides a ready-made alibi for Jat and other OBC communities to appropriate Rajput clans, symbols, and histories, on the grounds that they were never “genuinely” Rajput to begin with.

In other words, his theory of Rajput identity as a synthetic social fiction becomes a permission structure for appropriation—allowing others to claim that “these identities were never pure anyway,” thereby justifying cultural & identity annexation in the present. This mirrors the approach of Jatland-style propaganda, which thrives on a hybrid of Marxist fluidity and populist caste pride—simultaneously denying Rajputs their history while inflating their own.

2. Dr. Manisha Chaudhary, an Assistant Professor of History at Delhi University, has been associated with Jat-centered caste advocacy and regional literature. Her works contribute to the soft narrative of Jats as both historically “victimized” and simultaneously heroic—mirroring the political duality noted earlier. As an academic closely associated with Jat literary and cultural circles, Manisha Chaudhary exemplifies a newer strand of caste-identity historiography that blends ethnic nationalism with caste pride, particularly in the case of Jats. Her work projects a racialized and exaggerated account of Jat history, portraying the community not merely as a dominant caste but as a civilizational force, whose origins lie in the Eurasian steppes—conveniently evoking a mix of Indo-European, Aryanist, and pastoral imagery to frame the Jats as proto-rulers of India.

Despite aggressively asserting Jat ownership over ancient kings, martial traditions, and even Rajput clans, Manisha Chaudhary has consistently dismissed allegations of cultural appropriation, especially when it comes to Rajputi symbols, dress, or customs.

A striking example of this is her repeated justification of Jat adoption of “Rajputi poshaks” (traditional Rajput attire for women) in Haryana and Rajasthan. Instead of acknowledging this as appropriation of a distinct cultural heritage, Chaudhary downplays the issue, suggesting that “all communities in the region wore such dresses”—a historically inaccurate claim

Manisha Chaudhary and the Mihir Bhoj Identity Dispute: At Scroll.in, Dr. Chaudhary commented on the emergent clash in Kaithal (July 2023) over the identity of Mihir Bhoj—a ninth-century Rajput ruler claimed by both Gujjars. She said:

“Historically, we don’t have any clarity regarding whether Mihir Bhoj was either a Gurjar or a Rajput … unless we’re aware of his background, we can’t [confirm] … It’s just politics of the modern day that requires you to prove the caste, not in the ancient times.”

Political Neutrality or Willful Aporia? . By stressing historical ambiguity, she endorses the redefinition of Rajput historical figures as belonging to dominant OBC castes—without confronting the moral or cultural cost. Her treatment of the Mihir Bhoj controversy is emblematic of how modern caste historiography normalizes shape-shifting appropriation, advancing one community’s opportunistic political claims at the expense of another’s recorded ethnic history.

3. Dr. S.K. Chahal (Kurukshetra University) – A frequent contributor to Jat caste journals and regional history publications, Dr. Chahal has promoted the narrative of Jats as original rulers and Kshatriyas, often projecting Rajput clans like Tomars and Chauhans as offshoots of Jat lineages. He made headlines during the July 2023 Kaithal statue controversy by declaring that caste identities “seemingly blur when dived deeper into history”, and that modern disputes over Mihir Bhoj’s identity are “an outcome of modern-day politics and have nothing to do with history.

While caution is welcome, Chahal’s categorical dismissal of caste labels—even when epigraphy and inscriptions clearly identify Mihir Bhoj as a Pratihara Kshatriya king—serves to neutralize Rajput claims, conveniently leveling the field for competing appropriation by Gujjar or Jat groups. Ignoring inscriptions and genealogies that secure Mihir Bhoj’s identity as a Rajput effectively silences the Rajput perspective, placing all communities on equal argumentative footing—despite the historical weight favoring Rajputs

These scholars have enjoyed platforms in universities, journals, and cultural institutions, thus providing institutional legitimacy to what is essentially a politically motivated rewriting of history.

VI.The Case of Jhunjha Jat :History Invention For Urban Lebensraum

In recent years, a myth has gained traction in parts of Rajasthan and Haryana: that the city of Jhunjhunu was founded by a mythical figure named “Jhunjha Jat.” This claim, aggressively promoted by Jat caste-based YouTubers, coaching classes, and regional politicians, is a classic case of invented history for caste supremacy—a tactic aimed at erasing Rajput and Muslim Rajput legacy from the historical record and replacing it with Jat-centric folklore.

Contrary to this fabrication, Jhunjhunu was founded in the mid-15th century by Nawab Mohammad Khan, a Muslim Chauhan Rajput of the Kayamkhani subclan. The Kayamkhanis were originally Hindu Chauhan Rajputs who converted to Islam during the Delhi Sultanate period and rose to prominence as regional rulers in Shekhawati and northern Rajasthan.

Nawab Mohammad Khan established Jhunjhunu as the capital of a semi-autonomous Kayamkhani principality, well before it came under the later control of the Shekhawat Rajputs in the 18th century. This lineage and founding are well-attested in Mughal-era records, bardic genealogies, and British gazetteers. There is no historical reference—textual, inscriptional, or oral—to any “Jhunjha Jat” having founded or ruled Jhunjhunu at any point.

1. The “Jhunjha Jat” Myth: Digital Folklore as Caste Politics

Despite the clear historical record, a fabricated version of history has emerged through:

- Jat-oriented coaching centres that feed aspirants with caste-centric general knowledge booklets falsely stating that Jhunjhunu was founded by “Jhunjha Jat.”

- YouTube influencers and Facebook pages that glorify this invented figure, complete with doctored images, unverified folk tales, and caste pride slogans.

- Jat politicians and local leaders who repeat the myth at public events to assert symbolic caste ownership over civic spaces.

This distortion is not innocent folklore—it is a political project, aimed at appropriating symbolic capital and erasing Rajput (and Kayamkhani) historical presence in Shekhawati.

2. Why It Matters: Erasure Through Invention

- Caste Supremacy: It advances the narrative of Jats as original rulers, undermining both Rajput and Islamic syncretic legacies.

- Territorial Symbolism: Cities and place-names carry prestige. Claiming their origin is a way to assert caste dominance over a region, particularly in electoral or local panchayat contexts.

- Digital Normalization: Once the narrative is seeded through social media, it becomes difficult to reverse, especially among the youth preparing for exams or involved in identity politics.

VII. Imitative Expansion: Gujjars and Ahirs Following the Jat Template

The success of Jat historical appropriation has inspired similar tactics among other dominant OBC castes:

1. Gujjars now claim descent from the Gurjar-Pratiharas, despite the fact that Pratihara refers specifically to the Parihar (or Padhiyar) Rajput clan, not the pastoralist Gujjars. This historical misappropriation was actively enabled by the RSS and Jat BJP leaders, most notably Sahib Singh Verma, then Chief Minister of Delhi, who renamed a road as “Gujjar Samrat Mihir Bhoj Marg”, institutionalizing the distortion in public memory.

2. Ahirs similarly attempt to claim Yaduvanshi Kshatriya identity due to the semi-mythical Yadav figure Krishna’s association with cattle-herding. But the early medieval Yaduvansh (Yadava) line, in Sanskrit tradition, clearly refers to the Jadaun Rajput clan of Braj, not to the dominant Ahir caste—making this another case of myth-based identity appropriation.

Together, these appropriations have further destabilized Rajput historical space, as OBC groups seek to colonize Rajput legacies for contemporary caste-political advantage, often with the tacit or active support of dominant ideological forces.

VIII. Sociopolitical Impact on Rajputs

For Rajputs, the consequences of these layered distortions have been severe:

- Their identity as Kshatriyas is undermined, not through debate, but through hostile appropriation. Rajputs are delegitimized as “Samantvadi oppressors”, even as their lineage is stolen.

- Their dynasties and warriors are co-opted into alien caste genealogies, causing identity confusion. Their heroes are appropriated, their culture reframed, and their historical role minimized.

- Their youth are alienated from their own past, with textbooks and popular media painting them as either feudal villains or irrelevant relics.

- Their political clout is diluted, as OBC power blocs consolidate through fake shared ancestry and anti-Rajput populism.

- Politically, Rajputs are trapped between Brahmin-Bania upper-caste dominance and OBC-caste coalition hostility led by Jats, Gujjars, and Ahirs.

Conclusion: Historical Lebensraum as a Caste Weapon

The Jat approach to history is not merely revisionist; it is expansionist and extractive. It mirrors the German idea of Lebensraum—space acquired by conquest, not inheritance. In this case, the conquest is symbolic and historical: stealing clans, lineages, symbols, and narratives to displace the Rajputs from their own past.

This distortion is not simply academic—it shapes electoral outcomes, state policies, caste coalitions, and even grassroots violence. And it is precisely why Rajputs must invest in reclaiming, recording, and protecting their historical identity with scholarly rigor, cultural institutions, and political assertiveness.